When my daughter’s preschool teacher asked to make an appointment with me, I assumed perhaps my three-year-old had poked a hole in her classmates’ fantasy: Did she tell them that there is no Santa Claus?! The situation was much more egregious, her teacher informed me. She had told her classmates the truth: their grandparents will die, their parents will die, and one day they too will grow up and die. I was rather proud actually that my toddler had done so well confronting her mortality and thought her memento mori to be very Saint Nicholas-like.

It is not often that we pair the skull with our celebration of Saint Nicholas (as we rightly do with beloved Jerome), yet, during the Advent season, what could be more appropriate than reflecting on death? The man who invented Christmas, or rather re-invented it, Charles Dickens, gets it right, showing Scrooge’s contemplation of death as the necessary preamble to embracing the spirit of Christmas. Dickens sets “Santa” as the jolly ghost of Christmas present, couched between the past and the grim reaper. On the night before Christmas, Ebeneezer is confronted not by one spirit, for Santa Claus alone could do nothing to transform his cold heart to flesh and blood again. What was needed to convert “bah-humbug” into generosity and selflessness was three spirits, including that of the future, a spirit that forces Scrooge to look upon his own tombstone. A Christmas Carol opens with the announcement, “Jacob Marley was dead, to begin with,” foreshadowing that death will be a necessary part of this Christmas story. When Scrooge declares that he will honor Christmas in his heart, he rightly adds, “I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future.”

Part of the mystery of Advent—one that proves a barrier for some evangelical Christians—is that we are waiting for Jesus Christ’s birth, while the historical event has already occurred. The Christian liturgical year asks us to live in kairos, to wait for what has already come. Yet, the Advent season is not only for waiting for the first birth but also for the second, for the apocalyptic return of Christ. It is the season that celebrates the past, the present, and the future. And, during this season, we also decorate our home with lights, recite “Twas the Night Before Christmas,” sing “Here Comes Santa Claus,” and wear gaudy sweaters with garland and bows. The question that faces all American Christians should be—which practices shape my spirit towards the true inventor of Christmas and which are too tainted with commercialism and false myths to be virtuous? Which practices deserve the bah humbug of Scrooge and the scorn of the Grinch? More to the point, should believers in Jesus Christ also believe in Santa Claus?

Dickens arrived in America during Christmas 1842 and published his A Christmas Carol on December 19, 1843. His story wrestles with the experience, as biographer Les Standiford depicts in The Man Who Invented Christmas, which was adapted into a film in 2018. Formerly intrigued by American democracy, Dickens became disenchanted on his visit, finding Americans “overbearing, boastful, vulgar, uncivil, insensitive and above all, acquisitive.” Ebeneezer Scrooge embodies all that Dickens found wrong with Americans. Then, his demons are exorcised on Christmas Eve, in part, by an American-influenced Santa Claus. “The Ghost of Christmas Present” dons a robe of green trimmed with fur, wears a crown of holly and icicles (allusive of Christ’s thorny crown), and sits perched atop a cornucopia of roast meats, mince pies, cakes, and so forth. He holds a horn of plenty, carries a sheath without a sword, and like an ancient prophet or teacher, travels barefoot. If Dickens had visited America merely 20 years prior, he would not have been able to create such an icon.

Most of us assume our version of Santa has had a centuries-old life, but his red coat, white beard, and rosy cheeks are rather recent. A few years ago, my father bought me a copy of William J. Bennet’s The True Saint Nicholas, to ensure I passed on to my children a belief in Santa Claus. Bennet outlines the biography of Saint Nicholas, the history of his cult following, and the metamorphosis of his adoration that occurs following the Reformation. Bennet traces our recent caricature of the saint to Clement Moore’s 1823 poem “Twas the Night Before Christmas,” when the seminary professor tied the celebration of Saint Nicholas to December 24th instead of December 6th. Moore choose Nicholas’s ensemble “dressed all in fur” because of the popularity of John Jacob Astor, the fur merchant, and he stole the pipe and finger aside the nose idea from Washington Irving’s satirical History of New York. Irving was intent on teasing John Pintard, a wealthy philanthropist who chose St Nicholas as patron saint of the New York Historical Society, and by extension, New York. Pintard also declared the saint’s day to be a New York City holiday. These artistic renderings all affected Dickens’s transformation of Father Christmas from a thin, elderly figure to a jolly giant in green fur. When political cartoonist Thomas Nast (who gave us our Republican elephant and Democratic donkey) depicted Santa Claus for Harpers Weekly in 1863, he drew upon these forebearers, casting Santa’s robe red instead of green to align with the American flag, and choosing the North Pole as Santa’s home, because of the recent American fascination with it. By the 1900’s, American businesses adopted the gleeful version of Saint Nick: Macy’s first rolled out their Santa in the Thanksgiving parade in 1924, followed by Coca Cola’s Santa ads in 1931, and of course, the numerous Norman Rockwell Christmas cards and such that ensued.

Because of Santa’s commercialization by American culture, the Vatican converted his saint’s day to optional (though the Orthodox Church still reveres Saint Nicholas), and many Protestants worry that believing in Santa means choosing between America or Jesus. The most-watched films of December usually revolve around encouraging Americans to re-claim their belief in Santa Claus. In Miracle on 34th Street, a lawyer must prove in the US Courts—where all truth is debated and decided—that Santa Claus is real. In November 2019, Netflix released their first animated feature-length picture, and they chose Santa Claus for their subject matter. They titled it “Klaus.” The title choice indicates that the writers know how their theme is overdone, and they want to revive it. Calling Santa Claus “Klaus” reminds me of C.S. Lewis’s confession from Surprised by Joy, when he, as a young atheist, thought “it extremely telling to call God Jahveh and Jesus Yeshua.” The “saint” signifier has been removed from the name, of course, so that we may get down to the reality of things, but they keep the one-word name to retain the mystery. As the film ends, the man himself disappears, like Elijah or Enoch being carried into heaven, only this jolly old prophet follows the light that leads to his deceased wife. And, miraculously, Klaus’s spirit unexplainably continues to accomplish the generous deeds that he undertook in life. In “Klaus,” the revamp of the Santa Claus myth defines love accurately as “selfless” and reprimands the antihero, a young postman named Jesper, for his Ayn-Randian desire to do good to benefit himself.

Not that I explained all of this underlying philosophy to my children when we watched it. What works about the film is what works about all good Christmas movies—when the hero of the story is actually more saint-like than heroic, exhibits selflessness, surrenders his objectives to the needs of the community, speaks the truth boldly, loves the un-loveable. Think of What a Wonderful Life, where the town gathers around George Bailey and saves him from bankruptcy and suicide. Or, many of the Grinch adaptations, where the alienated outsider gives up his vendetta, so he can sing and carve the roastbeast. As Bennet writes, “Yes, Santa Claus is sometimes overexposed and exploited. But anything good is open to being exploited.”

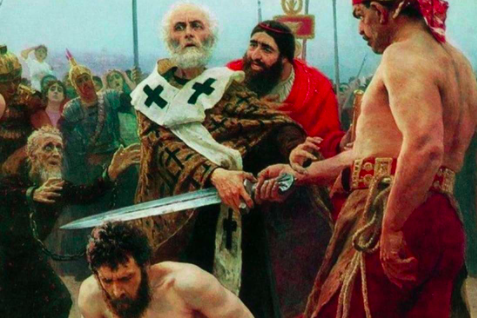

The problem is not believing in Santa Claus, but rather seeing Santa Claus apart from his past as Saint Nicholas as well as our future as saints. Saint Nicholas was a historical saint, a man whose boldness to speak against greed, generosity to the poor, and miraculous ability to withstand persecution deserves remembrance. When I visited St. Petersburg in 2011, I toured the Mikhailovsky Palace and saw a painting depicting one famous moment in Saint Nicholas’s life. Bennet describes it in his book. A corrupt magistrate accepted a bribe to sentences three innocent men to death: “The victims were only moments away from execution. Nicholas rushed to the center of town . . . strode up to the executioner and grabbed the sword from his hand.” The bishop freed the innocents and then confronted the magistrate, “Evil man!” While the magistrate tries to point the finger elsewhere, Nicholas does not allow him to blame others. He retorts, “It is your own greed for silver and gold.” The accusation aligns with Milton’s warning in Paradise Lost. Moments after Adam and Eve fall, they begin pointing fingers at one another: “neither self-condemning / And of their vain contest appeared no end.” The mark of the fall is to assign blame elsewhere, but the saint acts like God’s icon, showing us, through his eyes, our greed and fault.

In the painting, Saint Nicholas resembles an icon. His eyes look out beyond the scene (looking like he is dead to the world) as he grabs the sword from the bare-chested executioner. Others are in profile; no one else faces the viewer directly. He appears blind, as though he sees more than the rest of us, as though he sees evil and goodness as they are, versus our deflated sense of them. His stole is disheveled, so that we can imagine his haste to intervene, and the crosses in its pattern have been lifted up to outline his face.

The convicted are so unlike the elves or little cherub children that usually accompany a Santa Claus portrait that I feel silly even placing them in comparison. These innocents fated for death are partially dressed, one has his feet turned inward, and they bare ghastly expressions. To the worldly mind, these people do not look worth saving. As that thought crosses my mind, I place myself before the sword: would I have appeared worth saving? I recall the painting being the size of a whole wall, as though I could step right into the action, as though, if the sword had not been stopped by Nicholas, it would have swung out of the frame and sliced through my own neck. Facing this depiction of Saint Nicholas, we do not long to sit on the sainted figure’s knee. None would have the audacity to tell this figure what she wants for Christmas to be wrapped with sparkly paper and placed beneath their tree.

In a poem reflecting on this painting, Jacob Stratman[1] offers a litany of myths about Saint Nicholas, ones his wife discovers as she Googles: “how [the saint] calmed / the storm as he journeyed to the Holy Land, / how he saved a man from prostituting / his daughters by throwing gold pieces / through the window and running away / into the shadows, about his penchant / for anonymity, his penchant to save / to stave the sword meant for the innocent.” The verbs tied to Saint Nicholas show us a different figure than our Santa Claus—one who calms, journeys, saves, and staves the sword. Instead of adjectives such as jolly, fat, red-cheeked; instead of being defined by cheer, this saint is revered for his action, for his selfless and audacious, perhaps scandalous, good deeds. Stratman titles his poem, “A Poem for My Wife, Sitting at the Computer Thinking About Our Sons,” which sounds like an unsuitable description. Yet, the poet draws together the mundane with the sacred, the mystery of the timeliness of Advent with Christ’s timelessness.

In Stratman’s poem, he reveals his wife’s search is in late September because she is “already there / in love in anticipation in [her] head,” eager for the time to wait. In a New York Times piece printed the day before Advent, Anglican priest Tish Harrison Warren reminds us that this season asks us to face the darkness before the birth of light: “Advent holds space for our grief, and it reminds us that all of us, in one way or another, are not only wounded by the evil in the world but are also wielders of it, contribution our own moments of unkindness or impatience or selfishness.” We need this season to focus on the “sword always in the shadows,” writes Stratman, “always swinging above their heads.” How does our view of Christmas change when we dwell on the sword more than the stockings? When we try to steady ourselves beneath the piercing stare of the saint as we wait with hope for the coming of the newborn King? A vision of Santa Claus set between this figure of the past and the future that lies ahead of Christians redeems the domesticated and commercialized version.

In this middle of the last century, in protestation against the American version of Santa, a group of French priests hanged an effigy of Father Christmas and set it on fire in front 250 wide-eyed Sunday school children. Talk about memento mori. As much as I applaud scandalizing our children appropriately that they may denounce the evils of the world and love the Lord, I would advise keeping the fire in the hearth this Christmas. Instead, re-read Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (or watch the Muppets version, which has the bonus of Michael Caine dancing). All of Dickens’ stories are parables reminding Christians to fight greed and ignorance, to love and forgive, to live more for holiness than happiness. Most especially, his Christmas story shows us that Santa is real; his spirit of goodness should be embodied all year round. But, so is Saint Nicholas real, and so is Death.

“Remember that you will die,” my toddler tells her thumb-sucking classmates. And, then, Saint Nicholas rejoins, “But if you die, then you will live.” God bless us, everyone . . .

Read “Santa Is Real, But He’s Dead (to the World)” by Jessica Hooten Wilson on the Church Life Journal here.